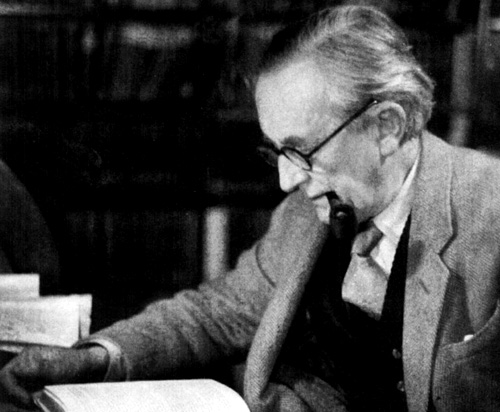

On this day in 1892 in the heart of what is is now modern day South Africa, J.R.R. Tolkien was born. Over the course of his life, he famously created an entire universe and the characters that have run through them which command a gigantic following around the world. On intoning his name, it seems impossible to not be swept into the world of elves and mountain eagles, of Nazgul and Balrogs, of hobbits and of dwarves.

But this isn’t a blog about Lord of the Rings, although that might feature. This is a post about Tolkien’s day job as a professor of English at Oxford University. Moreover, this is a post about a lecture that Tolkien gave on one fine day in 1939 on fairy stories.

Tolkien was fed up. He was fed up of modern society seeing fairy tales as being for children: of the idea that a fairy tale is for kids:

“It is usually assumed that children are the natural or the specially appropriate audience for fairy-stories … Is there any essential connexion between children and fairy-stories? Is there any call for comment, if an adult reads them for himself? … Fairy-stories banished in this way, cut off from a full adult art, would in the end be ruined; indeed in so far as they have been so banished, they have been ruined.”

Tolkien didn’t see any reason for this banishment to the nursery, however. He saw fairy stories as still a legitimate part of the literature landscape and should be treated as such. Fairy stories don’t need to be populated with Tinkerbells- rather:

“A “fairy-story” is one which touches on or uses Faerie, whatever its own main purpose may be satire, adventure, morality, fantasy. Faerie itself may perhaps most nearly be translated by Magic — but it is magic of a peculiar mood and power, at the furthest pole from the vulgar devices of the laborious, scientific, magician. There is one proviso: if there is any satire present in the tale, one thing must not be made fun of, the magic itself. That must in that story be taken seriously, neither laughed at nor explained away.”

Why am I bothering to tell you these things? For two reasons. First, it’s refreshing to read his own philosophy that lay behind all that he wrote. He really had it all worked out. However, there is a second reason: that I think reading this essay now shows how far Tolkien has come to make us appreciate the world of Faerie in our literature.

Tonight, I went to see the Royal Shakespeare Company’s production of The Tempest in Stratford-upon-Avon. The Tempest, written by Shakespeare in 1610-11, is set on an island dotted in the middle of the ocean, where the rightful Duke of Milan, Prospero has been stranded with his daughter for the past twelve years. Prospero, who from his study of his books has gained magical powers, conjures a storm that brings his scheming brother to be shipwrecked on the island and so controls their movements for the rest of the time that they are there as these shipwrecked nobles stumble through this island enchanted with invisible spirits that can send you to sleep, that can unveil your darkest fears, that can destroy you in all possible ways.

Shakespeare uses Faerie in this play as the central plot device. Throughout the play, the magic of Prospero and his ability to command the sprites around him, especially Ariel, drives the plot forwards. Prospero’s magic is not portrayed as being “laborious, scientific, magician.” Rather, it is seen as the crux of scholarly learning that has come from Prospero’s continued study of his books. Nor is his magic “neither laughed at nor explained away.” Those who know of Prospero’s power know he cannot be destroyed easily, and few try to argue with him. This is a play that inhabits the world of Faerie as Tolkien would see it. This is a play which is a fairy story.

Tonight, however, the theatre was packed with those looking to engage with this fairy story, not as a kid’s story, but as a serious piece of literature. They wanted to understand The Tempest as saying something meaningful about human experience and human emotion, in spite of being pretty sure that we’re not going to run into a sprite like Ariel when we next go out walking in the park. The play itself has come to have a large re-appraisal during the twentieth century, and is now thought of as one of Shakespeare’s greatest plays.

Was part of this re-appraisal due to the boy born in South Africa 125 years ago? Has Tolkien’s extensive writings on wizards and orcs made us more receptive to using the world of Faerie to understand our own human experience? Did the move toward fantasy which Tolkien spearheaded mean that now we’re more ready to accept sprites such as Ariel? Perhaps- I really couldn’t tell you. But I hope that we’re a little bit more receptive to the world of the Faerie in our literature, and no longer see a fairy tale as a story populated with 12 inch tall blonde things (although, I do also like Peter Pan. But that’s for another day).

Tolkien’s essay, ‘On Fairy Stories’, can be found here.

For a further, more detailed discussion of the essay, please click here.

For a copy of the text of The Tempest, please click here.